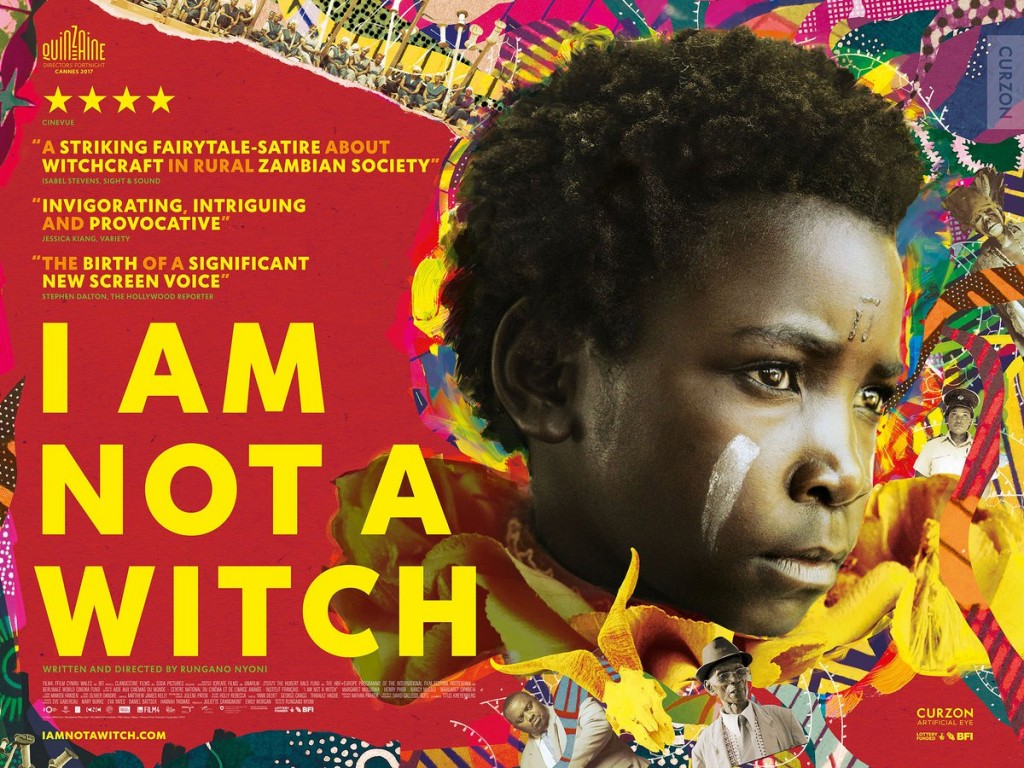

Film Review: I Am Not a Witch

Taciturn orphan Shula (Maggie Malubwa) is hauled before the police in a remote Zambian village, accused of practising witchcraft. The evidence is scant. Owing to her quiet demeanour, locals have attributed random petty incidents and bad dreams to her apparent malevolence. Little Shula is banished to a countryside compound where much older alleged witches are also confined. The other detainees take a maternal interest in the newest arrival. Unable to assert or prove her innocence, Shula is faced with a Cornelian dilemma; either she remains in the camp by accepting the allegations against her, or is cursed with turning into a goat if she attempts to escape.

In reality, it’s a psychological tactic to force the women to toil the land unpaid and be put on show for tourists. They are tethered to the camp by ironically pretty ribbons should they decide to chance a caprine fate.

Spotting an opportunity to make a quick buck from Shula’s non-existent powers, ambitious senior civil servant Mr Banda (Henry B.J. Phiri) ferries her around the region to pronounce judgements at Kangaroo courts and make TV appearances. Meanwhile, Banda’s wife Charity (Nancy Murilo), herself still living with the stigma of purported sorcery, develops a strange surrogate mother relationship with her husband’s new cash cow.

Talented British-Zambian filmmaker Rungano Nyoni’s beautifully bizarre debut feature, ‘I Am Not a Witch’ toes a delicate line. It could provide an opportunity for Western audiences to feel a smug compassion for the benighted African and their self-defeating superstitions. On the surface, the film does (satirically) play to those sentiments. Yet on a deeper level it’s a scathing, universally applicable commentary on how easily the powerful – of either gender – can exploit those whom society has discarded. No one really cares about the veracity of the accusations levied against Shula and her fellow poor and vulnerable inmates. They are mere inconveniences to be put out of sight. It makes no difference if a woman speaks up or remains docile and compliant, as Charity encourages Shula to be. She’s damned either way.

The hilariously pompous Banda, despite his peculiarities, could be any opportunist with the power and/or status to domineer those who do not have a voice. The film also underlines misogynistic double standards in Shula’s world. Male sorcerers are not only tolerated, they are revered; free to roam and be as lucrative as they wish.

Shula (a mature and endearing performance by young Malubwa) makes the most of the little agency she has, sometimes to the detriment of others. However, the stakes are so much higher for her than her bumbling captor. There is little, if anything, for Shula beyond captivity.